L’appel à communications pour le colloque annuel de la SEAA 17-18 de 2022 est désormais disponible. Vous pouvez consulter la page dédiée au colloque ici.

Une version pdf de l’appel à communications est aussi disponible ici.

Du fait des circonstances exceptionnelles du printemps 2020, l’appel à communications pour le colloque 2021 de la société a été prolongé jusqu’au 20 juillet. Vous trouverez plus d’informations sur le colloque et l’appel à communications ici.

« L’invention de l’humanisme commence avec une réflexion sur le signe et s’achève avec l’invention de sa symbolique. »

Anne-Élisabeth Spica, Symbolique humaniste et emblématique (1996, 44).

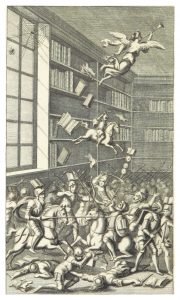

Dans l’introduction à l’ouvrage Texte et image dans l’Antiquité, Jean-Marc Luce affirme qu’« il y a un enchaînement des mots et des images au fondement de notre fonctionnement cognitif. Ce constat conditionne la rencontre entre texte et image ». C’est peut-être pour cette raison que les utilisations conjointes de l’image et du texte sont communes à tant de cultures et de civilisations au cours des cinq derniers millénaires, des hiéroglyphes égyptiens aux bandes dessinées contemporaines. Cependant, ce n’est sans doute qu’avec l’avènement de l’humanisme au seizième siècle que ce mode discursif se fera matrice de l’épistémologie d’une époque tout entière. Outil de prédilection des humanistes dans leur quête pour retrouver un langage universel pré-Babel, l’alliance du texte et de l’image dans le symbole (étymologiquement « qui unit, qui met ensemble ») est investie au seizième siècle d’un pouvoir didactique, rhétorique, et surtout dévotionnel considérable. « Le symbole », souligne Élisabeth Spica, « c’est la nouvelle alliance que les hommes passent avec Dieu. »

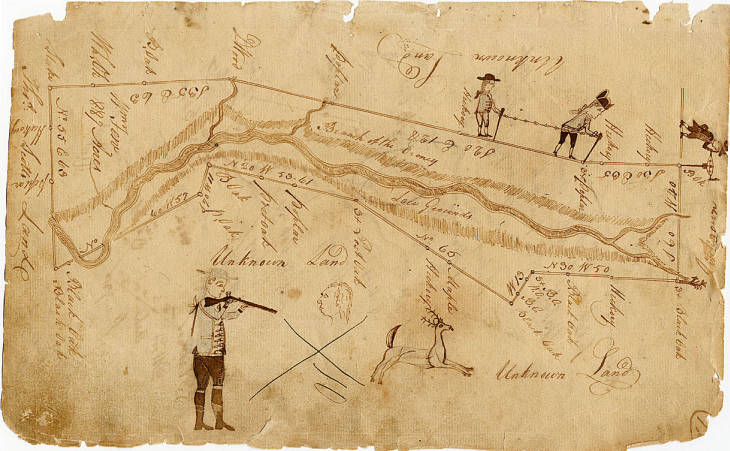

Bien avant les emblèmes de Whitney en 1586 et ceux, moins connus, de Thomas Palmer en 1566, des ouvrages dévotionnels usant de compositions texte-image circulent déjà en Angleterre, tels que le catéchisme illustré The Mystik Sweet Rosary of the Faythful Soule publié en 1533 par un auteur inconnu. Mais c’est surtout pendant les premières décennies du dix-septième siècle que les genres qui combinent les deux codes sémiotiques connaîtront un essor et une popularité sans précédent. Outre les recueils d’emblèmes à proprement parler de Peacham, Quarles, Hawkins, Lupton, Jenner et Wither, qui s’inspirent de l’Emblematum liber du juriste milanais Andrea Alciat (Augsbourg, 1531), les bestiaires illustrés d’Edward Topsell constituent un autre exemple fascinant attestant de cet engouement pour l’alliance entre le texte et l’image.

C’est seulement au milieu du dix-septième siècle, avec l’avènement du matérialisme et de l’empirisme, que le symbole perd progressivement sa valeur épistémologique absolue. Après le « désenchantement du monde », l’iconologie et la symbolique s’orientent progressivement vers une raison d’être plus esthétique et illustrative. L’association texte-image se pose alors en d’autres termes, auxquels cette journée est également consacrée. Les caricatures et illustrations de William Hogarth (1697-1764) ou le Little Pretty Pocket Book de John Newbery (1770) posent les jalons d’une nouvelle culture de l’illustration que poursuivront, à la fin du dix-huitième siècle, des artistes tels que Thomas Bewick et Thomas Rowlandson.

Nous nous proposons d’investiguer les diverses manifestations de l’intermédialité texte-image, en limitant le champ d’étude aux mondes anglophones afin d’inscrire cette journée dans le projet de recherche quinquennal de l’équipe organisatrice, Savoirs dans l’Espace Anglophone : Représentations, Culture, Histoire (S.E.A.R.C.H.).

Les communications pourront porter, entre autres, sur les thématiques suivantes :

† Les divers modes combinatoires de l’image et du texte dans les pays anglophones (emblèmes, devises, imprese, héraldique, illustrations, …)

† Les modes de translation d’un médium à l’autre (ekphrasis, prosopopée, référence à des motifs visuels dans le texte, représentation visuelle d’éléments textuels, etc.)

† Les outils théoriques et méthodologiques pour penser la frontière entre l’image et le texte dans les mondes anglophones (histoire des théories de l’image, transmédialité et intermédialité, sémiotique, études comparées de textes et d’image, histoire de l’art, etc.)

Cette liste n’est cependant pas exhaustive.

Les communications pourront être présentées en français ou en anglais, et ne devront pas excéder vingt minutes. Les propositions (300 mots maximum) devront inclure un titre et quelques éléments biographiques (100-150 mots), et devront être envoyées à l’adresse je-renaissance-strasbourg-2019@gmail.com avant le 15 octobre 2019.

Bibliographie indicative:

Barkan, Leonard, Mute Poetry, Speaking Pictures, Princeton University Press, Princeton, Oxford, 2013.

Bath, Michael, Speaking Pictures. English Emblem Books and Renaissance Culture, Longman Publishing, New York, 1994.

Couton, Marie, Fernandes, Isabelle, Vénuat, Monique, Jérémie, Christian éds., Pouvoirs de l’image aux 15e, 16e et 17e siècles, Éditeur Presses universitaires Blaise Pascal, Clermont-Ferrand, 2009.

Drysdall, Denis, « Authorities for Symbolism in the Sixteenth Century », in Peter M. Daly and John Manning éds., Aspects of Renaissance and Baroque Symbol Theory 1500-1700, AMS Press Inc., New York, 1999, 111-124.

Dyrness, William A., Reformed Theology and Visual Culture, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2004.

Engel, William E., Loughnane, Rory, Grant, Williams, The Memory Arts in Renaissance England: A Critical Anthology, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2016.

Farmer, Norman Kittrell, Poets and the Visual Arts in Renaissance England, University of Texas Press, Austin, 1984.

Gombrich, Ernst, The Uses of Images. Studies in the Social Function of Art and Visual Communication, Phaidon, Londres, 1999.

Ionescu, Christina, Schellenberg, Renata, Book Illustration in the Long Eighteenth Century: Reconfiguring the Visual Periphery of the Text, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, 2015.

Manning, John, The Emblem, Reaktion Books, Londres, 2002.

Mitchell, W.J.T., Iconology: Image, Text, Ideology, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Londres, 2013.

Rajewsky, Irina, « Intermediality, Intertextuality, and Remediation: A Literary Perspective on Intermediality », Intermédialités (6), 2005, 43–64.

Spica, Anne-Élisabeth, Symbolique humaniste et emblématique, Honoré Champion, Paris, 1996.

Umbach, Maiken, « Classicism, Enlightenment and the ‘Other’: thoughts on decoding eighteenth–century visual culture », Art History, vol 25, 2002, 319-340.

Vuilleumier Laurens, Florence, La Raison des figures symboliques à la Renaissance et à l’Âge Classique, Librairie Droz S.A., Genève, 2000.

Wagner, Jean-Marie, « Théorie de l’image et pratique iconologique », Baroque, 09-10, 1980. Web. Mis en ligne le 15 mai 2013, consulté le 25 juin 2019. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/baroque/520

Wolf, Werner, The Musicalization of Fiction: A Study in the Theory and History of Intermediality, Rodopi, Amsterdam, 1999.

*****************************************************

Postgraduate study day

Ut Pictura Poesis – “Making Text and Image Interact in the English-Speaking World Between 1500 and 1800”

Friday 20 March 2020, Université de Strasbourg

“The invention of humanism began with a reflection on the sign and ended with the invention of its symbolic system.”

— Anne-Élisabeth Spica, Symbolique humaniste et emblématique (1996, 44)

In his introduction to Texte et image dans l’Antiquité, Jean-Marc Luce writes that “words and images linked together lie at the heart of our cognitive functioning. Only on the basis of this observation can texts and images meet” . This may explain why the use of texts and images together has been common to so many cultures and civilizations over at least five millennia, ranging from Egyptian hieroglyphs to contemporary comic books. It is only with the advent of humanism in the 16th century however that this mode of expression became the epistemological matrix of an entire era. As the humanists’ instrument of choice in their quest to retrieve a universal, pre-Babelian language, the blending together of texts and images through symbols (meaning “that which unites, throws together”) was endowed with a considerable didactic, rhetorical, and devotional power at the time. “The symbol,” Spica underlines, “was the new alliance that Man made with God.”

Devotional works resorting to text-and-image combinations, such as the anonymous illustrated catechism The Mystik Sweet Rosary of the Faythful Soule (1533) were already circulating in England well before Geffrey Whitney’s emblems (1586) and their lesser known predecessors completed in 1566 by Thomas Palmer. However, it is during the first decades of the 17th century that literary genres based on the union of these two semiotic codes flourished and enjoyed unprecedented popularity. In addition to the emblem books published by Peacham, Quarles, Hawkins, Lupton, Jenner and Wither, which were inspired by Milanese jurist Andrea Alciato’s Emblematum liber (Augsburg, 1531), Edward Topsell’s illustrated bestiaries are another fascinating example that testifies to the growing interest for the joint use of texts and images at the time.

In the middle of the 17th century, with the advent of materialism and empiricism, symbols progressively lost their absolute epistemological value. Following “the disenchantment of the world” [4], iconology and symbolism gradually acquired a more aesthetic and illustrative raison d’être. The relationship between texts and images would henceforth rest upon a new philosophical paradigm which this study day aims to explore as well. Caricatures and sketches by William Hogarth (1697-1764) or John Newbery’s Little Pretty Pocket Book (1770) laid the foundations of a new culture of illustration that artists such as Thomas Bewick and Thomas Rowlandson further developed at the end of the 18th century.

We welcome contributions addressing the manifold instances of text-image intermediality. We would like to restrict the geographical scope of the papers to the English-speaking world, so as to make this study day fit in with the area of research in which the organising research team (S.E.A.R.C.H. : Savoirs dans l’Espace Anglophone : Représentations, Culture, Histoire) specialises.

Topics may include, but are not limited to:

† The various types of text-image combinations in English-speaking countries (emblems, devices, imprese, heraldry, illustrations, etc.)

† The modes of translation from one medium to the other (ekphrasis, prosopopoeia, references to visual motifs in the text, visual representations of textual elements, etc.)

† The theoretical and methodological tools through which to apprehend the border between texts and images in the English-speaking world (history of image theory, transmediality, intermediality, semiotics, comparative studies of texts and images, art history, etc.)

We invite abstracts of up to 300 words for 20-minute papers, in French or in English. Please submit your abstract along with a title and a short biographical note (100-150 words) to je-renaissance-strasbourg-2019@gmail.com by 15 October 2019.

L’appel à communications des Journées Jeunes chercheurs 2019 de la SEAA 17-18, de la SFEDS et de la Société d’Études du XVIIe siècle, organisées en partenariat avec le Centre de Recherches Anglophones (CREA, EA 370) et l’Institut de Recherches Philosophiques (IRePh, EA 373) est disponible ici.

Ces journées se tiendront à l’université Paris Nanterre, les 26 et 27 septembre 2019

L’appel à communications pour le prochain colloque annuel de laSociété d’Études Anglo-Américaines des 17e et 18e siècles, qui aura lieu les 17 et 18 janvier 2020 à l’Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne est désormais disponible.

Vous pouvez consulter la page consacrée au colloque annuel ici.

Vous pouvez également télécharger l’appel à communications en format PDF ici.

The 2019 SAES conference will question the complex notion of ‘exception(s)’, a concept which finds particular resonance within seventeenth and eighteenth-century studies. We invite papers and panels to ponder the notion of exception as the precursor of renewal and change, often ‘the unthinkable, the eccentric and the transgressive’.

An exception is dual by nature, condemned by some as a mistake, an erroneous and temporary deviation from the norm whose model it challenges, but hailed by others as the trailblazing sign towards new artistic, political and religious directions. In this atelier, we will question the status of the exception as the harbinger of transformation.

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, attempts at stabilizing the world through the conception of norms and the application of rules seemed proportionate to the many upheavals of the dominant codes of the time. The era developed a marked interest in the careful policing of exceptions and the theorizing of the rules governing all aspects of the world. Political thinkers, poets and artists tried to unlock the timeless rules by which the world was governed, from Locke in his Essay Concerning Human Understanding to the work of grammarians striving to shape the English language clearly (Hermes, James Harris, 1751), or Adam Smith and his theorization of economics. Yet the idea of the exception seemed constantly to emerge, it evoked an escape from rules and conventions which no longer applied. When in 1754 Hogarth published The Analysis of Beauty, attempting to give a template to the artists of the day through which to achieve harmony, he wrote that ‘it is a constant rule in composition in painting to avoid regularity’. Either in literary circles, with the development of the novel and its refusal to comply with any genre of the time, or in artistic terms, with the emergence of new schools claiming to represent modernity, exceptions appeared to dictate the new direction of taste and style.

Such tension between the stability fostered by rues and the change heralded by exceptions to those rules was felt sharply in both British and American political and religious institutions. After the Reformation, English Catholicism was no longer the norm but rather an exception, an anomaly to be eradicated. Later, the civil wars of the 1640s sent a legitimate monarch to his death and his heirs into exile, whilst conferring power to a man of lowly extraction and bringing down the unity of the established Church of England. Later still, the Glorious Revolution entirely rewrote the criteria for royal legitimacy, and installed a foreigner on the throne. Such changes were all deeply transgressive of long-established norms, and their outcomes would have been unimaginable to many of their contemporaries. Similarly, the American Revolution, while deeply influenced by British thought and philosophy, eventually became a transition towards the shaping of a new American identity, based on an ever-growing feeling of exceptionalism and a sense of national destiny.

In a broader geopolitical context, the multiplication of upheavals and wars, sometimes spanning several continents and the transformation of European and overseas territories led to the emergence of revolutionary states, which in turn questioned the very nature of exceptionality, since a revolution is by definition a state of exception supposed to bridge the gap between two stable regimes. Yet the idea of a revolutionary spirit, at the turn of the nineteenth century, had become less of a transgression and more of a manifesto of youth and renewal.

Transgression of norms and rupture with tradition thus heralded new eras and produced new norms. The establishment of an American Constitution following the Philadelphia Congressional Congress of 1787 as well as the ratification of a Bill of Rights formalized these new norms, transforming a revolutionary moment into a model for other nations, and the Founding Fathers into rule makers rather than rabble rousers. The historians both of America and of the British Isles contributed to the fashioning of a narrative of exception for their respective nations, building what has since been debunked as a Whig myth of greatness and unity which, whilst hailing the elect nation as exceptional, in fact took care to homogenize and normalize what it meant to be ‘American’ or ‘British’. But in the process, such historiographies entirely neglecting those at the margins of that grand narrative, such as those outside of the established Protestant norm, or those outside of normative reproductive heterosexuality, or women, the young, the poor, the natives, Afro-American peoples, or any group standing outside a norm which was white, male and Protestant.

How then can an exception be defined? Is it but a transition between two norms, or the impetus for the creation of new ones? Can its transgressive aspects be digested and included into the new templates it creates? Self-defining one’s art, society or religion as an exception necessitates the conception of an identity in constant flux, and the possibility of an endless revolutionary state. Yet exceptions both defy and define norms in their time, by creating either a reaction or a school of thought. An exception can thus appear as a prophet for the new, but also as a limiting category in which transgression, instead of being encouraged, is paradoxically enshrined.

Papers will not exceed 25 to 30 minutes maximum.

Proposals of 300 words (in English, in Word.doc format), accompanied by a brief bio-bibliography, should be sent to Laurence Lux-Sterritt and Sara Watson by 1st November 2018 at: laurence.sterritt@univ-amu.fr and sara.watson@univ-amu.fr

Papers will be considered for publication in the Varia of XVII-XVIII (25,

List of topics for papers / panels (non-exhaustive):

– Exceptions and exceptionalism

British and American revolutions as exceptions, templates or transitional states

States of exception in political history of the period

-Exceptional spaces

A new world order creating spaces of exception inside European Empires (colonial exceptions)

Globalization and transmission of models of exception: are revolutions contagious?

-The exception in literature and art: oddity, transition or establishment of the new norm?

The question of new literary forms emerging during the period and their relationship to older established forms

Modernity versus tradition in art

Deliberate literary transgressions and the emergence of new manifestos

-Religious exceptions and revolutions

New religious minorities and exceptions during the 17th century

The transition from exception to establishment

This seminar invites individual papers or panels of two or three speakers to explore the concepts of exception and exceptionality in early modern history and literature. It would like to gather researchers specialising in history, literature (theatre, poetry, prose) and visual arts to reflect these concepts in context and in connection and contrast with current understandings of these notions. The seminar also wishes to observe the actual nature of normative rules and models and how much they were followed politically, aesthetically, socially and religiously. It will analyse how the early modern era relied on exception as a method of improvement of normative rules.

The seminar welcomes proposals dealing with exceptionality from a legal, political and theological point of view. In the wake of Diego Pirillo’s forthcoming study of The Refugee-Diplomat: Venice, England and the Reformation (Cornell, 2018), we would like to focus on political, religious, commercial and artistic agents, women and men working both “within and outside formal state channels through underground networks of individuals who were able to move across confessional and linguistic borders, often adapting their own identities to the changing political conditions they encountered”. Papers may focus on exceptional individuals (scientists, writers, painters, politicians, religious refugees, dissenters etc) in exceptional situations and the consequences of such exceptionality on political, social, sexual and religious norms. This exceptionality should be seen in terms of gender and social ranking as well as of confession. Cross-borders literary and non-literary perspectives are also welcome.

Subsequently, papers are invited to discuss the concept of tolerance and the evolution from comprehension to toleration. It also examines early modern criticisms of toleration such as George Wither’s views of toleration as conspiracy in Prince Henry’s Obsequies (1612) and the development of a rhetoric of exclusion in literary and non-literary texts.

As the barriers between literature and history did not exist in the Renaissance, this seminar will naturally explore how art and, in particular, theatre and poetry contributed to these philosophical and political debates. It will examine how early modern male and female artists promoted or opposed exceptions and exceptionality to change aesthetic views and practice. For Keir Elam, theatre “allow[s] the individual’s context to be alienated and an alternative state of affairs to be perceived as more immediately real.” (The Semiotics of Theatre and Drama). Papers may consider then how the visual arts and literature made use of exceptions and exceptionality to question mimesis on a purely aesthetic level but also on the political level. The example of Shakespeare’s reconfiguration of the views on beauty in the wake of the sonnets to the dark lady should lead to a study of the ways the early modern era either encouraged or debunked normative and conservative views of gender, race and sexuality. It will raise the question of the fluctuating views of exemplarity and regularity during the early modern era.

Notwithstanding the importance and the impact of exceptions and exceptionality, the papers may also explore the limits of this concept in terms of our understanding of the early modern era. Peter Brook writes that “all the exceptions blur the truth” (The Empty Space), and we should also reflect on the limits of exceptionality in terms of political as well as aesthetic agency and of our vision and the representation of history. The seminar thus invites reflexive contributions on how contemporary visions on the Renaissance turn the early modern era into an “exceptional” era which some would blindly emulate, and others would dismiss altogether. This debate applies both to the strict content of early modern studies and the place of the Humanities in today’s episteme, but also to the place of early modern studies in the Humanities today.

List of topics for papers / panels (non-exhaustive):

– Tolerance, Toleration and Exceptions: from Comprehension to Exclusion

– Religious and territorial diversity in early modern polities (government, representation, local and geopolitical perspectives)

– Literary discussions of comprehension, toleration and exception (religious, territorial, sexual diversity in theatre, poetry, prose)

– Radical iconoclasm as a major feature of English religious identity (visual arts)

– England and exceptionalism: from toleration to exclusion

-Early Modern Theatre and Rule-Breaking: The Poetics and Politics of Exception on the Stage:

-When the exception is the rule: making exceptions, creating new norms?

-Off-centering normative performance: staging early modern drama anew (anti-traditionalist theories and performances…)

-The theatre exception: an exceptional space for new epistemes

-Norms and exceptions: rethinking norms and normality

– The rule of exemplarity? : the evolution of role models in early modern literature and history

– Discussing early modern views of regularity

-Debunking Normative Beauty: The Exception of the Dark Ladies in Early Modern Literature

-From Petrarchan beauty to Black is Beautiful

-Poetry and stage performance then and now

– “Exceptional and Unacceptable” (Elizabeth Honig, “Lady Dacre and pairing by Hans Eworth”, Renaissance Bodies): The Agency of Early Modern Women on the Political and Cultural Stage

-The cases of Bess of Hardwick, Arbella Stuart et al. as art dealers and political intermediaries

-Early modern women writers and their actual agency: exception, transgression and renewal

-New approaches to teaching and researching Renaissance Studies (History and Literature)

-Shakespeare, the Canon of the Exception: from exception to norm to exception again.

-Early Modern Studies in the contemporary world: the limits of exceptionality

Papers should be no more than 25-30 minutes long.

Please send proposals of individual papers (250 words) or two-to-three-paper panels to Nathalie Rivère de Carles (nrivere@univ-tlse2.fr) and Jean-Louis Claret (jean-louis.claret@univ-amu.fr

DYNAMIQUES DES HÉRITAGES (XVIe-XVIIIe siècle)

Appel à communications

Montpellier, 18-19 octobre 2018

Colloque annuel des jeunes chercheurs de la Société Française d’Étude du XVIIIe siècle (SFEDS), de la Société d’Études Anglo-Américaines des XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles (SÉAA XVII-XVIII), et de la Société d’étude du XVIIe siècle.

Organisation 2018 : Institut de Recherche sur la Renaissance, l’âge Classique et les Lumières (UMR 5186 du CNRS, Université Paul-Valéry Montpellier 3)

Loin d’être une donnée figée dont les individus et les groupes hériteraient, un legs qu’il faudrait conserver en l’état, le passé constitue pour chaque époque un enjeu majeur. Comme le montrent les études récentes sur les écritures de l’histoire et la mise en valeur des patrimoines, les héritages culturels répondent à des dynamiques complexes.

Ce colloque permettra tout d’abord d’interroger la façon dont les œuvres et les pratiques du passé ont été perçues jusqu’à la fin du XVIIIe siècle, chaque époque réinventant ses origines et son identité. On s’intéressera aussi aux représentations des XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles jusqu’à aujourd’hui, y compris dans l’éducation et les médias. Enfin, ces rencontres, destinées prioritairement aux jeunes chercheurs mais ouvertes à tous, seront l’occasion de poser une série de questions théoriques concernant les représentations du passé et leurs fonctions religieuses, sociales, artistiques, etc.

Ce colloque permettra tout d’abord d’interroger la façon dont les œuvres et les pratiques du passé ont été perçues jusqu’à la fin du XVIIIe siècle, chaque époque réinventant ses origines et son identité. On s’intéressera aussi aux représentations des XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles jusqu’à aujourd’hui, y compris dans l’éducation et les médias. Enfin, ces rencontres, destinées prioritairement aux jeunes chercheurs mais ouvertes à tous, seront l’occasion de poser une série de questions théoriques concernant les représentations du passé et leurs fonctions religieuses, sociales, artistiques, etc.

Les communications pourront notamment porter sur les aspects suivants :

– Les héritages culturels dans la littérature et dans les arts de l’âge classique et des Lumières : écrire le passé à l’âge classique, le rôle des modèles, inventer à partir du passé,…

– La réception des XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles dans la littérature, les arts et les médias ; enseigner la littérature et les arts de l’âge classique aujourd’hui ;…

– De manière plus générale, on pourra s’interroger sur la notion d’héritage culturel, l’intérêt et les limites du concept d’actualisation, les héritages et la cohésion sociale, les héritages et les conflits,…

Les propositions, en français ou en anglais, comprenant un résumé d’environ 250 mots et un bref CV, devront parvenir aux organisateurs au plus tard le 1er avril 2018, à l’adresse suivante :

jeuneschercheurs.ircl@univ-montp3.fr

Les repas de midi et le dîner du colloque seront pris en charge.

Les participants sont invités à se rapprocher de leur laboratoire de rattachement et de leur école doctorale pour le financement du transport et de l’hébergement.

Comité d’organisation :

Luc Borot (Pr civilisation britannique XVIIe siècle)

Linda Gil (maître de conférences en Littérature et histoire des idées XVIIIe siècle)

Florence March (Pr Théâtre britannique XVIe-XVIIe siècles)

Stéphanie Roza (chargée de recherche CNRS en Littérature et histoire des idées XVIIIe siècle)

Franck Salaün (Pr Littérature française XVIIIe siècle)

Jean-Pierre Schandeler (chargée de recherche CNRS en Littérature et histoire des idées XVIIIe siècle)

4 doctorants de l’IRCL

Appel à contributions

Colloque international de la Société d’Etudes Anglo-Américaines des XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles (SEAA 17-18)

18-19 janvier 2019 Paris

Organisé par Mme Armelle Sabatier (Paris 2, Law and Humanities/CERSA UMR7106) et M. Bertrand Vanruymbeke (Paris 8, TransCrit, IUF)

We are grown old; I am come back to England, being almost seventy years of age, husband sixty-eight, having performed much more than the limited terms of my transportation […], and he is come over to England also, where we resolve to spend the remainder of our years in sincere penitence for the wicked lives we have lived.

Daniel Defoe, Moll Flanders, 1722

Criminelle de haut vol exilée en Virginie, le personnage de Moll Flanders incarne les figures mythiques des criminels façonnées à la fois par la littérature des dix-septième et dix-huitième siècles, mais aussi par la presse de cette période. L’univers des criminels, leur profil, leurs relations avec la presse de l’époque ont fait l’objet de nombreuses études qui ont tenté, au travers d’un travail d’archives, de saisir la réalité des hors-la-loi, des condamnés, réalité souvent exagérée et déformée par des dramaturges tels que John Gay qui immortalise le criminel Jonathan Wild dans The Beggar’s Opera (1728), par les romans à sensations (par exemple, Captain Alexander Smith’s History of the Lives of the Most Noted Highway-men, Foot-pads, House-Breakers, Shoplifters and Cheats, 1714) ou encore par certains journalistes complices de ces fameux criminels. Certains historiens ont récemment étudié la réalité de la déportation des criminels anglais, écossais et irlandais dans les colonies tels que G. Morgan et P. Rushton (Eighteenth-Century Criminal Transportation, Palgrave, Macmillan, 2003), Gwenda Morgan et Peter Rushton (Banishment in the Early Atlantic World. Convicts, Rebells and Slaves, Bloomsbury, 2013) ou encore Elodie Peyrol-Kleiber (Les premiers irlandais du Nouveau Monde: une migration atlantique (1618-1705), 2016), sans oublier les travaux de Roger Ekirch (Bound for America. The Transportation of British Convicts to the Colonies, 1718-1775, 1987)

A la croisée de l’histoire sociale, juridique, de l’histoire coloniale, des études littéraires et visuelles, ce colloque international a pour but de réfléchir à la construction mythique, voire fantasmée, de la figure du criminel, véhiculée à la fois par les genres littéraires (la tragédie domestique du XVIIe siècle, le roman du XVIIIe siècle, par exemple), la presse, les gravures, les récits de voyage, la correspondance des colons et des administrateurs, les représentations picturales ou encore les comptes rendus de procès qui ne sont pas toujours fiables à cette époque. Le travail d’archive pourrait également éclairer la réalité des activités criminelles, mais aussi les rouages des systèmes juridiques anglais et ceux des colonies.

On pourra s’intéresser, entre autres, aux thématiques suivantes :

Les liens juridiques entre les îles Britanniques et ses colonies. Quelle est la réalité d’un forçat ou d’un esclave à cette époque ? Correspond-elle toujours aux récits ou témoignages ?

la figure de la sorcière très présente à la fois dans la littérature, la presse ou les comptes rendus de procès de cette époque. Où se situe la limite entre la réalité de pratiques condamnables et le fantasme d’une femme maléfique ?

Est-ce que les représentations d’un(e) criminel(le) varient entre les hommes et les femmes ? Existe-t-il des mythes, voire un fantasme, de la femme criminelle, qui auraient été favorisés à la fois par la presse et la littérature de la première modernité, mais aussi par certains historiens contemporains ?

Les pirates, ces figures de l’entre-deux mondes, demeurent les criminels les plus ambigus, à la fois héros et antihéros transatlantiques.

Comment se dessinent et se construisent la topographie et la géographie du crime ? Outre la capitale du crime qu’est Londres, existe-t-il des réseaux de criminels en province, dans les autres nations, mais aussi dans les colonies anglaises, voire françaises, portugaises et/ou espagnoles ? Quel rôle ont pu jouer la littérature à sensation et la presse dans cette géographie du crime ?

Quels sont les apports méthodologiques de la numérisation des archives aux études récentes sur les crimes et la criminalité aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles ?

Les propositions sur les autres figures criminelles, telles que les voleurs, les prostituées, les meurtriers et autres, seront également les bienvenues.

Les propositions de communications, en français ou en anglais, assorties d’un titre, d’un résumé de 300 mots et d’une notice biographique, sont à envoyer à l’adresse suivante : seaa2019@gmail.com

La date limite est le 20 mai 2018

Call for Papers

Crime and Criminals in the Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century Anglo-American World

An International Conference of the French Society for Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Studies on the Anglo-American World (Société d’Etudes Anglo-Américaines XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles SEAA 17-18)

Organisation: Armelle Sabatier (Paris 2, Law and Humanities/CERSA UMR7106) and Bertrand Vanruymbeke (Paris 8, TransCrit, IUF)

January 18-19 2019 Paris

Confirmed keynote speaker : Professor Trevor Burnard (University of Melbourne)

Abstract

We are grown old; I am come back to England, being almost seventy years of age, husband sixty-eight, having performed much more than the limited terms of my transportation […], and he is come over to England also, where we resolve to spend the remainder of our years in sincere penitence for the wicked lives we have lived.

Daniel Defoe, Moll Flanders, 1722

Returning from exile as a convict in Virginia, Daniel Defoe’s Moll Flanders embodies the mythical figure of the English criminals deported in the colonies, who were made popular by seventeenth- and eighteenth-century literature and the press. Archives have given access to criminals’ profiles, relationships and networks, enabling historians to draw a more accurate picture of their lives and activities that were distorted and refashioned in drama, such as John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera (1728), featuring one of the leading figures of the underworld, Jonathan Wild, in sensational novels (e.g, Captain Alexander Smith’s History of the Lives of the Most Noted Highway-men, Foot-pads, House-Breakers, Shoplifters and Cheats, 1714) or in some reports by journalists who had connections with the underworld. Historians have also studied the deportation of English, Scottish and Irish convicts in the colonies (G. Morgan et P. Rushton (Eighteenth-Century Criminal Transportation, Palgrave, Macmillan, 2003, Gwenda Morgan and Peter Rushton, Banishment in the Early Atlantic World. Convicts, Rebells and Slaves, Bloomsbury, 2013, Elodie Peyrol-Kleiber (Les premiers irlandais du Nouveau Monde: une migration atlantique (1618-1705), 2016), Roger Ekirch (Bound for America. The Transportation of British Convicts to the Colonies, 1718-1775, 1987).

At the intersection of social, legal history, colonial studies, literature and visual culture, this international conference seeks to re-assess the mythical and imaginary constructions of the criminal figures in literature (e.g the 17th century genre of the murder plays, 18th century novels) the press, the visual arts, travel narratives/accounts or trial reports. Archives also prove to be an invaluable source of information to study criminal activities and the complex structures of the English legal systems and those implemented in the colonies.

Among the great variety of possible topics, participants may like to consider:

the legal relation between England and its colonies. How were convicts and slaves treated in these new territories over the period? Are narratives or accounts always reliable sources?

Witches are recurrently portrayed in varied media of the time, both literature and the press. What was the reality of these women’s imagined or supposedly illegal practices?

– Is there any variation in the way female and male criminals were portrayed in those days? May the press and literature, and even some contemporary historians, have distorted the representation of female criminals?

The figure of the pirates, travelling between different worlds and continents, remain highly ambiguous Anglo-American heroes and/or anti-heroes.

The geography of crime. Beyond the capital of crime that used to be in London, was there any criminal network in the rest of Britain and in the English colonies, maybe crossing the borders with other European nations such as France, Portugal and Spain? Did literature or the press account for this geography of crime?

What is the impact of new technologies on recent studies devoted to crime in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries?

We would also welcome contributions on other criminals such as thieves, prostitutes, murderers or any other criminal figures and/or any other aspect of this subject.

Potential speakers are invited to submit a title and an abstract of 300 words along with a brief bio-bibliography to seaa2019@gmail.com

Deadline for submissions is May 20th 2018